Viability since 1905

What does it

mean to have courage?

More mouths to feed

Toward the end of the 18th century, the fear of starvation increased. More food for more mouths to feed required more plant nutrition in the form of nitrogen. Natural fertilizers were no longer enough.

Easier said than done

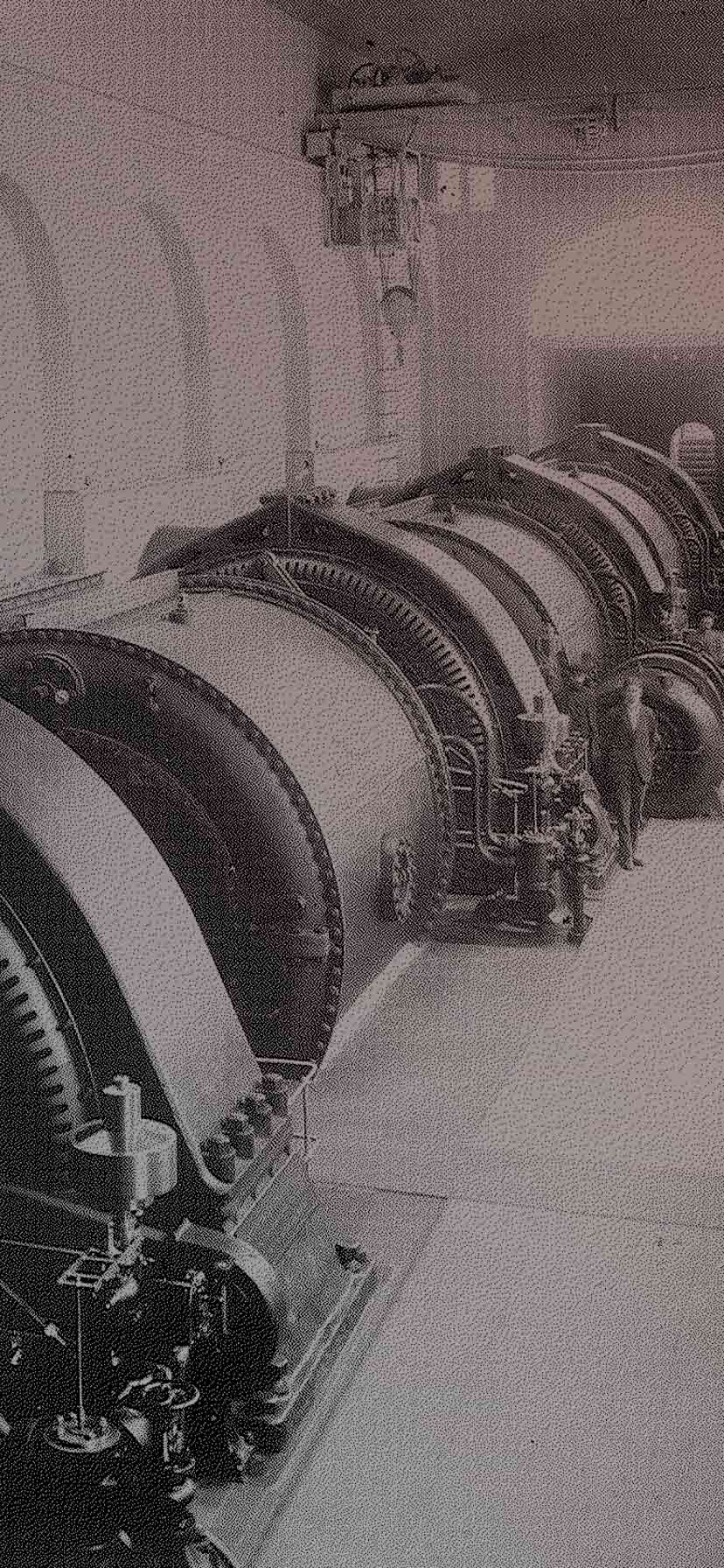

In theory, nitrogen could be produced on an industrial scale. Industrial giants around the world began eyeing a new market. They threw themselves into the competition. Brand new technology had to be developed. This turned out to be easier said than done.

Nitrogen from the air

A determined engineer with lots of Norwegian hydropower and a creative scientist found each other at a dinner party in 1903. With the help of a handful of young engineers they also found a solution: together they could bind the nitrogen in the air.

The wonder in Telemark

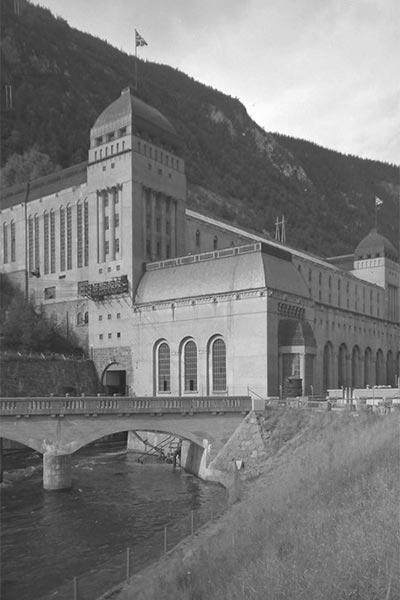

In 1905, they established Norsk Hydro. With power from Europe's largest hydropower plant, which they built at Notodden, the world's first industrial nitrogen fertilizer production began in 1907. A miracle had taken place in Telemark. A new industry was created. Today it is a World Heritage Site.

More money, more power

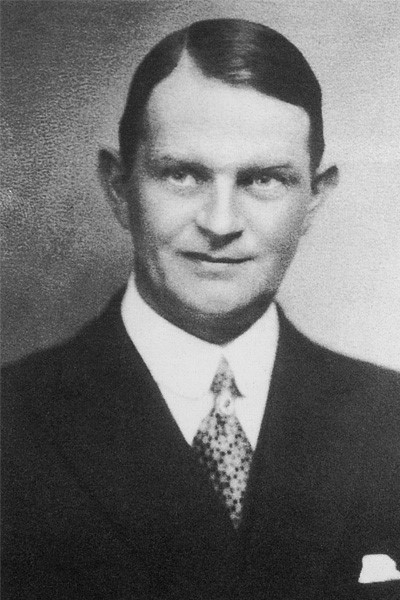

Huge investment in a small country. Industrial entrepreneur Sam Eyde traveled around the world to raise money. It turned out to be difficult. The initial capital came from the Wallenberg brothers in Sweden. Old acquaintances in Germany gave a thumbs down. Banque Paribas in Paris eventually provided the funding.

Initiative on land and at sea

Sam Eyde was supposed to be on the Titanic on its maiden voyage to America in 1912. He was delayed and left with the next boat. While he was en route, word reached him that the Titanic had struck an iceberg and sunk, with the loss of 1,500 lives. Eyde drew up a plan that was handed over to the commission of inquiry upon his arrival in New York. The result of his initiative was the "International Ice Patrol" which was active for over 100 years.

From mega success to aluminium

Sam Eyde's closest employee, Sigurd Kloumann (26), managed thousands of construction workers. They built a new industry, the world's largest hydropower plant, and new cities at Notodden and Rjukan. When success was achieved in 1911, though, the entrepreneur and the young engineer had a falling out.

A future in light metal

A frustrated Sigurd Kloumann travelled west, established Norway's first integrated aluminium company in 1915, developed more hydropower and created yet another small town: Høyanger. In 1917 he also started refining activities in Holmestrand and laid the foundation for successful businesses in canned packaging and aluminium cookware.

Competition from new German technology

Despite major investments in new and untested technology, Hydro was an industrial and financial success. After two decades, however, the company was in trouble in the face of new and more efficient German technology. Hydro was forced into the role of little brother and subcontractor to German industrial giants. It was a mixed experience.

A few decades of industrial history cannot be told in a few lines. If you want to find out more about Sigurd Kloumann or the World Heritage Sites of Notodden and Rjukan, click on the link below the images.

If you want to move on in our exciting history, into the "dirty thirties", the dramatic events during the war and the post-war boom, keep on scrolling.

Cooperation for better or worse

Cooperation was key when Hydro was founded. Cooperation on technology development. Cooperation on financing. Cooperation on construction. And cooperation on problem solving. For better or worse, cooperation is a recurring theme throughout the company's history.

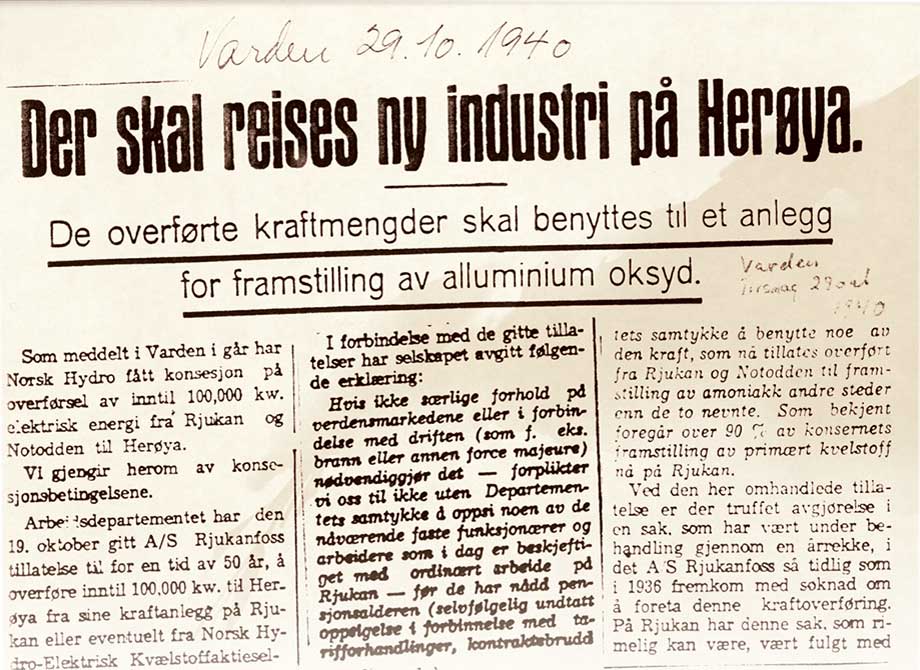

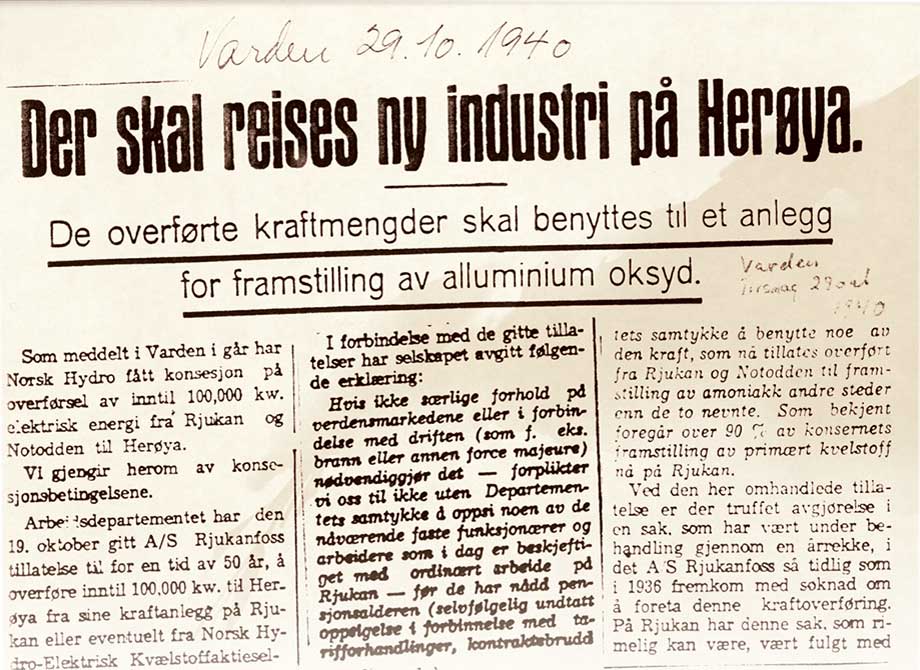

Hydro moves to the coast

The first result of the cooperation with the German industrial giant IG Farben was that Hydro built a new production plant on the coast. The new German production technology was introduced here. Herøya was soon to become Norway's largest industrial site, while production at Notodden was scaled back.

Dramatic labor conflicts

The interwar period was challenging. Financial losses, cost cuts, layoffs and pay cuts for those who had jobs. In 1931, Hydro became the arena for Norwegian history's most dramatic labor conflict: the Menstad battle at the plant between Skien and Porsgrunn. The police and military were deployed against striking workers. It was a valuable learning experience.

Clash during the war

During the war, a partially German-owned Hydro and Sigurd Kloumann's aluminium company would meet again. This happened with German help and was not a positive encounter for anyone involved. The management of both companies fought for the German occupier's favor. Both won in their own way, but lost their honor in the longer term.

Aluminium dream bombed into pieces

Sigurd Kloumann became a supplier of aluminium plates for the occupying power's fighter aircraft. At Herøya, Hydro collaborated with Hermann Göring's Luftwaffe to build a light metal plant. In 1943, the Allies put an end to Hydro's aluminium dream; 1,650 bombs killed 55 and destroyed the plants.

The battle for heavy water

Hydro's plant in Rjukan was bombed in 1943 and subjected to one of World War II's most spectacular sabotage operations in 1944. The target was a by-product of fertilizer production: heavy water. The Allies feared that the precious drops from Telemark County could help Adolf Hitler develop a nuclear bomb. This export was finally stopped for good when the railway ferry ‘Hydro’ was sunk on Lake Tinnsjøen.

Hydro became partly state-owned

During World War II, Hydro became more and more German. After the war, the German shares were confiscated by the Norwegian authorities. The Norwegian state thereby acquired majority ownership of Hydro. For a long period, the state owned more than half of the shares. Its ownership share was later reduced to a third.

The dream of diversification was realized

Ever since its founding, Hydro's management had dreamed of having several legs to stand on. All attempts at this failed. In 1951, on the ruins of the wartime production of aluminium, production began of magnesium and the plastic raw material PVC. These materials were used in everything from Volkswagen's popular Beetle to vinyl records by The Beatles.

Fully into oil and aluminium

After cautious diversification in the 1950s, Hydro sped up the process in 1963. The company switched from electrochemical to petrochemical production of fertilizers, began construction of a new aluminium plant in Karmøy and joined in the exploration for oil in the North Sea. The aluminium investment and oil exploration took place in cooperation with international partners.

Cultural revolution in the spirit of cooperation

Neither management nor workers was satisfied. In 1967, the unions in Herøya and Hydro's management initiated an innovative partnership. They tried out corporate democracy in practice. Employees at all levels were given greater responsibility. The experiments attracted attention and marked the start of a cultural revolution that had ripple effects around the world.

Oil discoveries in partnership

In 1969, Hydro was the only Norwegian partner when the first oil discovery was made on the Norwegian continental shelf. Within a few years, both Hydro and Norway experienced a new reality. Oil revenues and technology development laid the foundation for unparalleled growth.

The wheel came full circle in aluminium

Hydro grew dramatically in breadth and depth in the 1970s and 1980s. Much happened in cooperation with other companies. In 1986, Hydro acquired the Norwegian aluminium company Årdal and Sunndal Verk (ÅSV). The industrialist Sigurd Kloumann's aluminium businesses in Høyanger and Holmestrand were then united with the company he built up from 1905 onwards.

The cooperation does not stop here

Cooperation is no less important today. Our way of cooperating and interacting has evolved. Employees have gained greater influence, formally and informally. Employee organizations are actively involved in decision-making processes. Cooperation with the world around us has taken on new forms, and dialogue with customers, suppliers and other partners has become more important.

Caring – for what?

Caring is, among other things, about having a long-term perspective. Not least, it is about respecting the resources we depend on and that are given to us to serve the community of which we are an integral part. Dilemmas must be met with respect for people and the environment today and with respect for those who come after us.

Housing for employees

Right from the start, Hydro created several purely industrial sites, first at Notodden and Rjukan. Everything had to be built from scratch: housing for employees, infrastructure, schools and hospitals. Founder Sam Eyde invested heavily. Almost everything was built to a higher standard than normal. The goal was to create communities where employees and their families wanted to live.

Eight-hour working day

Seen from today's perspective, the working conditions and employment terms were not ideal. On May 1, 1918, Hydro's employees at Notodden and Rjukan protested for an eight-hour working day. The following day they took matters into their own hands, went home two hours before their working day was over – and won. The following year, the eight-hour working day was introduced into law in Norway.

The company doctor was met with distrust

In 1940, Hydro got its first company doctor. Eyvind Thiis-Evensen became a pioneer, conducting extensive research on employee health and working conditions, including the effects of shift work. The workers viewed him with distrust. Eventually, the occupational medical program was accepted and expanded with more doctors and male nurses.

Environmental improvements one after the other

In the 1970s, the environmental movement emerged. Many people asked questions about the environmental impact of the chemical industry. When Hydro's top management first took action in the 1980s, it did so with genuine enthusiasm. First at Karmøy, then at Herøya, operations were turned upside down. The results were remarkable.

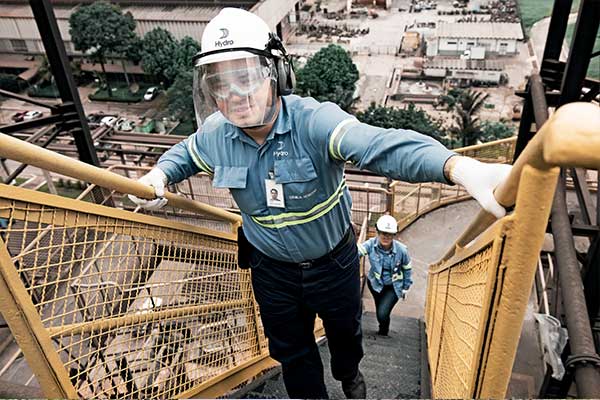

Increased focus on safety activities

Chemical production, high pressure and high temperatures could be a dangerous combination. In the 1980s, employee safety became a measure of the company's success. Hydro soon became a pioneer company. Environment and safety became a central part of the company's corporate culture.

Many businesses were sold

In the 1990s, the big conglomerates fell out of favor. Hydro, which had grown in many directions through the 1980s, began selling off businesses: explosives producer Dyno, chocolate producer Freia-Marabou, the world's largest fish-farming company Hydro Seafood, and the pharmaceutical companies.

The fertilizer business became Yara

Hydro's original core business, fertilizer production, delivered poor financial results in the 1990s. After a turnaround at the turn of the millennium, the business was spun off and listed on the stock exchange; in 2004, Yara International was the world's largest supplier of nitrogen fertilizers and has since further strengthened its market position.

Withdrew from oil and gas

In 2007, Hydro's oil and gas business was merged with Statoil, known today as Equinor. Hydro gained a dominant position on the Norwegian continental shelf and was an international leader in deep sea oil production. As an oil company, Hydro had made its mark as a technologically innovative operator.

100% aluminium

From 2007, after the petrochemicals business was also sold, Hydro was able to concentrate fully on aluminium, a business area where the company, through several major acquisitions – including ÅSV in Norway in 1986 and VAW in Germany in 2002 – had established itself as a leading market player.

100% integrated

In 2010, Hydro acquired the Brazilian mining company Vale's aluminium business and strengthened its position as a leading integrated aluminium company. This included large bauxite deposits and the world's largest alumina refinery, Alunorte. Following the acquisition of Sapa in 2017, Hydro also became a global leader in extruded products.

Not without challenges

In Brazil, Hydro soon encountered many challenges. In 2018, the company was accused of not taking seriously the environmental challenges at the large aluminium refinery in Barcarena. Operations were partially halted for over a year. Although the company contended that the charges were baseless, it was a costly reminder that trust must be built every single day.

The story doesn’t end here. Hydro has always had a long-term perspective. Not least when we continue to work toward even more sustainable production and products. Our goal, just like back in 1905, is a more viable society. Learn more about our history here.